“I call an animal, a species, an individual corrupt”, Nietzsche explains in The Antichrist, “when it loses its instincts, when it chooses, when it prefers what is harmful to it”. The author of Zarathustra forgot to add “a nation”. Indeed a little earlier, in Twilight of the Idols, he had explained that any morality in which self-interest withers remains, under all circumstances, a bad sign:

“This applies to the individual; it applies especially to peoples. Something essential is missing when self-interest begins to be lacking. Instinctively choosing what is harmful to oneself, being lured by ‘disinterested’ motives, almost amounts to a formula for decadence”.

Familiar words to lovers of German literature. In Robert Musil’s The Man Without Qualities, the Nietzsche enthusiast Clarisse will make use of this dictum in her bitter marital war with her weary husband Walter. Yet we are more likely to associate the motif with Buddenbrooks—the secret handbook of German self-abdication, the so-called “Book of the Germans”: that epic account of the decline of a Hanseatic patrician family and its loss of vital self-interest, of mercantile ruthlessness and instinct for its own well-being, luxuriantly celebrated as refined bourgeois decadence. The Buddenbrooks do not die of excess, but of insufficient egoism. When the instinct for one’s own good dies, all that remains is attitude—and attitude, as we know, is the last thing one can afford when one is going under. In Vienna, they know this.

The Buddenbrooks do not die of excess, but of insufficient egoism.

In Germany in the year 2026, the signs unmistakably point to collapse, or at least to decline. The political dwarf now seems to be turning into an economic one. The nation has drunk a lethal cocktail of moralistic self-aggrandizement and hysterical love of the faraway—a mix of intellectual decay, generally unfavorable circumstances, and self-intoxication through excessive convictions of ethical purity. Fanaticism, a demon to which Germans succumb all too easily, has the country in an iron grip. A happy ending is unlikely.

The Federal Republic of Germany is a peculiar country. Not all that long ago, during the 2006 Football World Cup, Der Spiegel celebrated the “Deutschlandparty” with narcissistic delight—and an allegedly purified, modern nationalism filled people’s hearts. Black-red-gold flags, pennants and stickers clung like a swarm of locusts to cars, houses and human beings. Unlike at the time of reunification, foreign observers seemed to indulge this little act of self-deception with benevolence. In what seems only a few moments later—namely today—people who wear national football jerseys, an unremarkable sight everywhere else in the world, are harassed and threatened at demonstrations and suddenly labeled national chauvinists or even “Nazis”.

Less than two decades after the World Cup in Germany, the Deutschlandparty, people who wear national football jerseys (an unremarkable sight everywhere else in the world) are harassed and threatened at demonstrations and suddenly labeled national chauvinists or even “Nazis”.

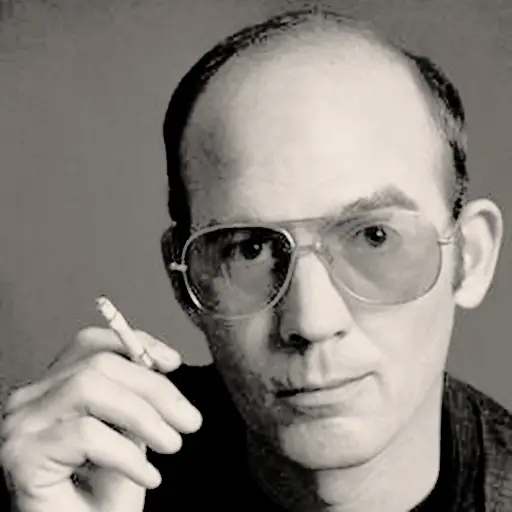

The author of that historic Deutschlandparty article, the former head of Der Spiegel’s culture section, Matthias Matussek (b. 1954), has long since stopped being invited to any parties at all and, out of spite, has defected to the hardline nationalist camp. Germany has too many converts.

A fanatical anti-nationalism has spread everywhere. But is that really so bad? From a liberal point of view, is it not bearable, perhaps even welcome? Is nationalism not a scourge of humanity, a modern form of an ancient curse woven into the fabric of human community itself? When the evolutionary biologist and human ethologist Irenäus Eibl-Eibesfeldt (1928–2018), a close friend and collaborator of Konrad Lorenz, lived for some time with a Stone Age–level indigenous tribe in Papua New Guinea, the tribal elders expressed a wish one day: they too wanted to fly in his large “magic bird”—the expedition’s airplane. A flight was generously promised for the following day. At dawn, the five most respected men of the tribe had gathered massive boulders around the aircraft. When the astonished expedition leader asked what on earth they intended to do with them, he was told they wanted to drop the rocks from above onto the tribe living in the neighboring valley.

For Oscar Wilde, patriotism was the virtue of the scoundrel; for Samuel Johnson, the last refuge of the rogue; and for common sense, all too often merely a cloak for base intentions. Anti-nationalism thus appears to consistent liberals almost as a prerequisite of noble sentiment. When Germany succumbed to national intoxication during the Wars of Liberation, even great minds were swept along. Goethe was not: Etiam si omnes—ego non. Nationalism seems to many cosmopolitans, not entirely unjustly, narrow-minded. When the youthful Ulrich in The Man Without Qualities claims in a school essay that the true friend of the fatherland does not consider his fatherland the best, the result, in relatively liberal Kakania, is a forced change of schools.

When the youthful Ulrich in Musil’s The Man Without Qualities claims in a school essay that the true friend of the fatherland does not consider his fatherland the best, the result, in relatively liberal Kakania, is a forced change of schools.

But here is the point: when one looks at German anti-nationalism in recent years, a striking shift in its social base becomes apparent. It used to be primarily the affair of small, intellectually shaped circles—educated cosmopolitans, left-wing theorists, student milieus, and anti-German cliques (as formed since the 1990s around magazines such as konkret and Bahamas). Today anti-nationalism increasingly presents itself as a broad, socially diffuse affect that reaches deep into the middle of society—all the way to simple minds from whom one would hardly have expected such a stance in the past.

To be sure, the earlier anti-nationalism, the intellectual plaything of a self-declared avant-garde, already displayed unpleasantly shrill, at times downright unhealthy traits—to the point of frenetically thanking the British officer Arthur “Bomber” Harris (1892–1984) for the bombing of Dresden. “Bomber Harris, do it again!”

Today classical intellectual anti-nationalism has mutated into a kind of cultural litmus test—an attitude regarded as morally clean and reasonable in large parts of the upper and middle classes, among younger generations, and in mainstream media. What was once a distinctive minority position has become a threatening mass phenomenon.

Today, anti-nationalism has mutated into a kind of cultural litmus test—an attitude regarded as morally clean and reasonable in large parts of the upper and middle classes, among younger generations, and in mainstream media.

Meanwhile, old-fashioned nationalism is by no means dead. A new, somewhat unappetizing party, the AfD, has raised its head and is being fattened by a moralistic, fatally anti-pragmatic government policy. Not so long ago, a then not-unpopular chancellor, Angela Merkel, refused during a CDU party convention to wave a small German flag as part of the mandated closing jubilation, apparently because it offended her sense of style. To this day, German nationalists irreconcilably resent her for it. Resentment seems to be a particular German talent—especially today. Nationalism and anti-nationalism are evenly matched in this regard.

Along winding, mysterious paths, the two even seem to be related, perhaps identical. Probably the most militant nationalist at present, Jürgen Elsässer, editor-in-chief of Compact magazine (which was briefly banned in Germany), himself regarded as a colorful oddity even on the right, was once a resolute anti-nationalist and anti-German. The slogan Nie wieder Deutschland (“Never again Germany”), it is said, came from his pen. Sahra Wagenknecht, who in 1996 co-authored the book Forward and Forget? with Elsässer, now increasingly adopts nationalist tones as well. The same applies to her geriatric husband, former SPD chairman Oskar Lafontaine, who after the fall of the Wall had warned against “national drunkenness”.

Not only is the situation complicated; so are the Germans—as Nietzsche already knew:

“The German soul has corridors and side corridors within it; there are caves, hiding places, dungeon vaults; its disorder has much of the charm of the mysterious; the German understands the secret paths to chaos”.

The feuding siblings nationalism and anti-nationalism agree, at most, on one point: their antisemitism, which they conceal behind the euphemism “criticism of Israel”. The circle has closed in a ghostly way: Zeitgeist or A Time for Ghosts.

Must Germany die? Hardly. We are already dead.